In my last post, I discussed the challenge we will have redesigning Higher Education pedagogy for the post-pandemic world. One of the specific issues will be identifying the good practice that has been developed in response to the COVID restrictions and keeping any practice that is better now than it was before. Sounds simple, but identifying “good practice” has always been challenging in teaching contexts even at the best of times. However, the nature of the pandemic will undoubtedly distort meaningful data – a fact I noted in my previous post.

Processes and practices are often at very different stages of development, which can make evaluating them challenging. If we can’t evaluate, then how can we decide where to continue investing effort?

Developing the I3 framework.

In reality, this challenge is nothing new. When I worked as an innovation consultant, this is one of the most common challenges we faced when working with business leaders. Companies would regularly know that they wanted to innovate but often didn’t know where they should focus their efforts, or (truly) where they were innovating already.

Part of my job was helping them to take stock and audit their current processes. By doing this we could identify where there was space (and capacity within the team) to innovate. There is a significant body of research in this area especially in the domain of management decision theory. However, most of the methods available were either too complex or not suited to the problem at hand.

Over a couple of years, I developed a framework to help make sense of a process landscape. The intention of the framework was to identify where a process was in its current state of evolution, and support decision making to further develop it. The framework was intentionally simple, helping decision-makers to quickly audit their activities.

I called this framework I3.

Over the past couple of months I have been thinking about how I3 could be used to take stock of our current teaching practices, as it is designed for making sense out of complex processes.

The I3 classifications

To avoid confusion; in this post, I will explain the way that I3 works. In most cases, I will talk about “processes” rather than “practices” (but feel free to use your own nomenclature). I make this distinction because a “teaching practice” is often made up of several smaller activities, I will be referring to these as processes.

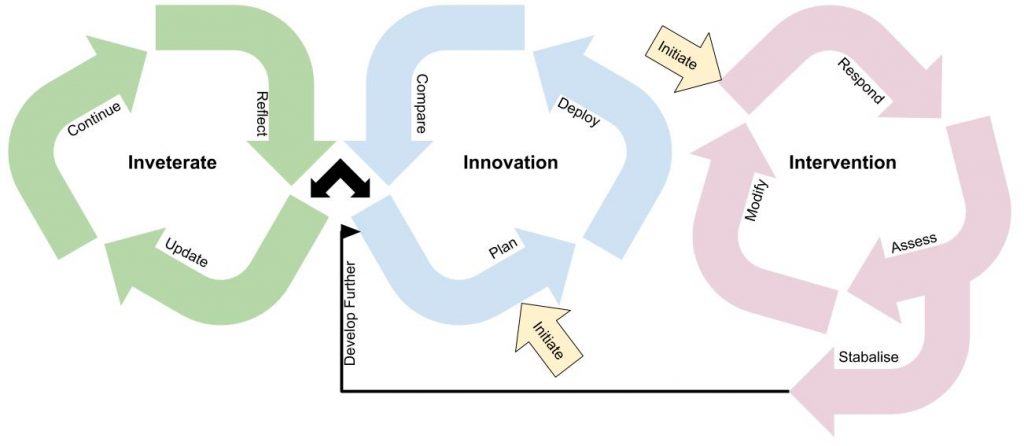

In I3 all processes are classified in one of three domains, these are Inveterate Processes, Innovative Processes, and Intervention Processes. Each of these domains has a specific lifecycle (implementation, and evaluation) approach.

Inveterate

The process of habit

Inveterate processes are ones that are deep-rooted, habitual, or long-standing. These are typical processes that suit a specific need, that we know work, and that we have not needed to change. An inveterate process is one that will have been used for a number of years, and is considered “standard operating procedure”.

Inveterate lifecycle

Inveterate processes should optimally follow this lifecycle.

- Reflect / The process is long-standing you should begin with a refletion. Is the process still working as you expect it to? Consider a range of perspectives in your reflections.

- Update / Based on your reflections, do any modifications need to be made?

- Continue / Take any previous reflections into account, but largely continue to implement the process as you have previously.

Evaluating an inveterate processes

Inveterate processes should be evaluated longitudinally, taking historical contexts into account. They are typically evaluated in an ongoing fashion against their own data in a “does this still work” fashion. A single poor (or exceptional) performance shouldn’t be considered sufficient to invalidate (or validate the approach). Confused? The metaphor I once used to explain this process to a colleague simplified it for them.

Imagine you go fishing at the same spot on the same river, every month for 4 years, and every time you go fishing you catch a fish. One day you go, and you don’t catch a single fish… this one event doesn’t mean that the river is empty, you don’t have enough evidence to abandon your spot on the river. You should still reflect on the disappointing performance, possible chat to some other fishers, but any update to your behaviour should be measured and proportional.

Reflections should be holistic and consider a variety of perspectives from a range of stakeholders. They should look external as well as internal; for example, as part of your reflection you should be looking at alternatives, what are other people/organisations in the same domain doing?

Sometimes you will decide to change, adapt, or modify your inveterate process. If this is a small change (maybe a minor update to reflect new technology) then you will probably continue in the inveterate domain. If it is a larger or more radical change, then you will probably move to an innovative process.

Innovation

The new idea

Innovation processes are activities which are radically different from an existing or accepted standard practice. They are typically implemented in response to a reflection such as something which needs to be significantly updated, or a new process to capitalise on a missed opportunity. An innovation process is one that is new to the organisation or specific context, but one that is strategically planned.

Innovation lifecycle

Innovative processes should optimally follow this lifecycle.

- Plan / Innovations should be planned in detail, with the specific reference to intended outcomes and how they will interact with other processes. Planning should cover how the innovation will be implemented and how it will be evaluated.

- Deploy / Implement the innovative process. A deployment schedule should include the ongoing monitoring and capturing of outcomes and deliverables, specifically “is this working how we expected it to?”

- Compare / Innovations will typically be implemented to replace an older inveterate process or to fill a specific need. The last point of the innovation lifecycle is to compare against the previous state. Either comparing against a previous process or compare against the absence of the new process.

Evaluating an innovative processes

Innovative processes (through their nature) lack historical data. As such they are evaluated by comparison to another process, or the absence of process. There are many ways that this can be implemented, for example:

- Comparison against the outcomes of the previous process. This is most appropriate when you have decided to go “all in” with the new practice.

- A/B testing – when you are able to test your innovation with an isolated application or group, testing without fully committing to the new process.

- Parallel testing – Implementation of two or more innovative processes in parallel comparing against the two.

Innovative processes are defined by the planning phase, which provides the opportunity to design a formal (detailed) evaluation. As innovative processes are inherently going to be changing (or replacing) something, there is a higher burden of responsibility in demonstrating that the new idea has value. This is due to the inherent risk in changing an established practise – you need to ensure that the risk is worth it.

Intervention

The rapid response.

An intervention process is one that is rapidly deployed, typically in response to a crisis. Interventions are typically deployed because something unforeseen has happened that demands an immediate response. They differ from an innovation as they lack a distinct planning phase. An intervention is sometimes best considered as “the best we could do, with the information, resources, and expertise we had available at the time”.

Intervention lifecycle

the Intervention lifecycle is distinct from inveterate and innovative processes as it begins with action.

- Respond / something has happened, which requires an immediate response. Use the experience gained from other processes to implement a response.

- Assess / Our ability to predict outcomes is limited, so the activity must be continuously assessed.

- Modify / Based on our assessments, modify the response as required. We mustn’t be precious about maintaining our response, agility, and the ability to modify based on new information is key to success.

Evaluating an intervention process

When we implement an intervention we are usually doing so in a crisis. We have not had the time to isolate our variables, collect useful data, and plan a substantive evaluation. You will generally struggle to formally evaluate an intervention for this reason. Perspectives can often be highly distorted based on the outcome too. Sometimes people will just be pleased that you managed to overcome the immediate challenge, and conversely, some people will be annoyed that their expectations were misaligned with reality.

Some of the poorest managerial decisions I have ever seen made were in response to a small amount of data regarding a short-term intervention. “This worked well, we should always do this”, or equally problematic “this went badly, who is responsible”.

Interventions instead should be closely monitored, and adapted as new information becomes available. If you tried solution A, and it didn’t work, what did you learn from implementing it? Will that new information help you to implement solution B? In many cases, with interventions we are attempting to fight fires, and sometimes select the least worst option.

The purpose of the intervention lifecycle is to maintain agility, and continuously adapt until you are able to stabilise the situation at hand. Using the limited data you have (including intuition, common sense, and experience) modify the process until more data is available and the picture becomes clear.

Once you believe you have a good understanding of the efficacy of an intervention (or the situation has been externally stabilised), you have a choice; you can either abandon the intervention and move back to your established process, or transition into an innovation.

Moving between I3 categories

In I3, each category runs as a cycle. For example, an inveterate process would run as a loop of “reflect, update, continue” for as long as you intend to use that particular process. However, processes can move between categories, and I have tried to explain that in the following diagram.

Lets look at how a process can move between categories.

An inveterate process could become an innovation process following the reflection stage of its lifecycle. For example, we may decide that a process needs a radical or substantial update. At this point, we would move it to the innovation category, and begin with a period of planning.

An innovation process could become an inveterate process following a positive evaluation. After an innovation goes well, we could decide to keep it as an ongoing practice. In this case, we would transition from the compare stage of the innovation cycle to the update state of the inveterate cycle. Of course, an innovation process can be initialised independently and doesn’t need to be spawned from an inveterate process.

Intervention processes are a little different, as they are only initiated independently. They are processes that are created as a direct response to an unforeseen or unprecedented event. However, if they are successful you may choose to stabilise them, and transfer them into an innovation process (which can be formally evaluated). I have often argued that chaos can be the foundry of innovation.

Both innovation and intervention processes can also be abandoned, which is typically referred to as reverting to the norm.

Why would you want to move between categories?

Good question! We can consider the three categories as sitting along a spectrum from ordered (inveterate) to chaotic (intervention). We typically want to be moving as many processes into the ordered space over time. And there are several reasons why.

The first reason is staff workload. Intervention processes are inherently more workload intensive. While an inveterate process may need updating once a year (for example) we may be updating an intervention on a daily basis. Organisations that get themselves caught in the trap of constantly putting out fires rarely have time to establish good practice, and never have the opportunity to truly innovate.

The second reason is evaluation. In the intervention space, we are typically working from incomplete data or often intuition. In the intervention space, we aren’t formally evaluating, giving us the evidence to develop best practice.

The final reason is cognitive load. New processes require significantly more attention, and this can burn out a team very quickly. I once described this as being on a lifeboat with someone running round with a pair of scissors. There are only so many holes you can patch before you get exhausted and give up. Organisations that try to change too much too quickly often find people quickly reverting to old (sometimes inferior) practices. Often because the team doesn’t have the “head-space” to keep 101 plates spinning at once.

Another advantage of tried and tested approaches is that people know them well. That means that there is a lot of experience and expertise within a team to support new colleagues (helping reduce transition issues).

The innovation space is crucial to help organisations adapt and evolve. We will often want to try a new idea, taking us out of the inveterate domain. That essential space between order and chaos is where companies can be creative. But it requires planning and the ability to commit time to explore a new idea properly. However, if your team is using up all their time (and cognitive load) fighting fires with interventions, they are going to want to keep other processes in the inveterate space. Put simply, we need established practices to give us the time elsewhere to innovate. That last sentence will probably preach to the converted – but looking at processes this way was often quite eye-opening for business leaders when I developed it.

I will close this section with a minor point of personal belief. In my experience, indecisive decision making is one of the key traits/predictors of poor leadership. If a change needs to be made, a delay can take away the time to plan, forcing a team into intervention rather than an innovation. Interventions will always be more time consuming and generally of lower quality. It is often safer to commit to a decision and start planning even if working with incomplete data. In my experience (having run a number of these audits over the years) most of the companies that were bogged down in interventions (leaving no time to innovate), were in that position due to indecisive leadership. As a note (as this often gets raised) being cautious is not the same as being indecisive, it is perfectly possible to be both cautious, and decisive. Caution is embedded in planning within innovation contexts, the classic adage of “assume the best but plan for the worst” allows people to work in the innovation space (without getting caught into a reactive intervention loop).

Using I3 in a teaching and learning context

So, now you know I3, how do you apply it to the problem at hand? How can we use the framework to pull out and develop best practice? Knowing which category each of your teaching processes are in drastically changes how you approach them, and how you identify the good practice that you want to keep. It also helps you to prioritise where you want to focus your attention – innovating where you can have the most impact – and freeing up time elsewhere.

By auditing your own processes from the last year you can start by identifying which inveterate processes you are using, where you are innovating, and where you have deployed interventions. This will tell you what your specific burden of evaluation is, and what you need to do next.

- Inveterate processes – continue to reflect/evaluate as you would normally.

- Innovation processes – use the data you have to do a detailed comparison. Look at your plan, did you meet the objectives as intended? If you did, decide if you either a) need to go through the innovation cycle again and further develop the idea, or b) if the process has delivered as expected, you could transition to an inveterate process.

- Intervention processes – you didn’t have time to plan, and you probably reacted to changes along the way. Look at the data you have, but go with your gut. Do you think there is something in your intervention worth developing into an innovation? If not, you should consider abandoning/reverting the process to free up space elsewhere.

However, to do this you must first have a breakdown of all your teaching processes. However, abstracting a complex teaching practice into a number of individual processes can be a challenge in itself. Fortunately, I have another framework/tool from my business days which can help make this easier. I have used this tool in my own teaching practice for a number of years.

However, that is another long discussion so I’ve saved it for another blog post! In this next post, I will talk about how to make sense of a complex pedagogy, break it into smaller processes… and discuss how students can be engaged in evaluation (in all 3 process categories).

See the next post in this series here

Please let me know your thoughts in the comments!

2 Responses

Thanks Chris very useful and well explained post!

Thanks Chris 🙂